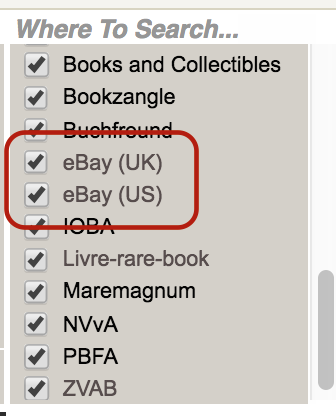

A few days ago, under the online banner “Amazon’s Curious Case of the $2,630.52 Used Paperback,” the venerable New York Times reported with surprise on phenomena we are all too familiar with: second hand books for sale at absurd prices. The first book in question was a 2009 romance novel, for sale on Amazon, entitled “One Snowy Knight.” Having brought this information to the attention of David Streitfeld, the Times’ respected Amazon authority, the author then innocently asked “How many really sell at that price? Are they just hoping to snooker some poor soul?” She then alternatively wondered whether Russian hackers might not have taken up the manipulation of used book prices to keep themselves busy during their spare time.

The answers to the questions are: 1-we will be astonished to ever see evidence that books with similarly absurd prices do actually sell, even on Amazon, and; 2- Russian hackers have better things to do, even when there are no elections available for them to subvert. The inflated prices reported in the the story are, almost certainly, the products of imperfect algorithms created to continually reprice products without any human intervention. Booksellers call it “robopricing,” a term of general contempt.

How this works and what it means for the future of second-hand bookselling is a dismal subject. I have already written a lengthy blogpost about it, which can be read HERE. I will refrain from going over it again. The New York Times article did, however, bring up a few interesting questions that I did not cover in my earlier post.

The focus of the Times piece was, of course, Amazon. Certainly the automated pricing tools are effective there, and it would be hard to argue that price adjustment is not a natural, even essential, part of retail sales. And when a price is obviously off the mark then it is probably due to a flawed algorithm rather than a scheme to fleece a naive and price-indifferent buyer.

But I am also wondering if there might not be more to it than that. Could there be other ways to benefit from putting a crazy price on a used book? In this case I couldn’t help but notice that the $2,630.52 bodice-ripper in question was out of print and the colourful tweet that illustrated the online version of the story made it a point to mention that a new reprint was scheduled for release in July. It can’t have been bad publicity for this news to appear on page B1 of the NYT when it did. Was it just a fortuitous coincidence? The author, Deborah MacGillivrary, is no ingénue in the art of influencing book sales on Amazon. Perhaps she has discovered some clever method for boosting the sales rank of a new book by drastically inflating the price of second-hand copies. If so, she is not letting us in on her secret.

However, someone from MacGillivrary’s publisher, Kensington, is also quoted in the story and prefers to point the finger of blame in a different direction. “Amazon is driving us insane with its willingness to allow third-party vendors to sell authors’ books with zero oversight… It’s maddening and just plain wrong.”

Streitfeld also sees culpability in the third-party sellers. He writes: “Amazon is by far the largest marketplace for both new and used books the world has ever seen… (Amazon) directly sells some books, while others are sold by third parties. The wild pricing happens with the latter.”

The problem with this is that third-parties are the only sellers of second-hand books on Amazon, which is only interested in selling new books on its own account. Without third-party sellers its book offerings would be limited to what is in print (or recently remaindered). At that point Amazon ceases to be “by far the largest marketplace for new and used books.” That status (which is quite arguable to begin with) would then belong to a metasearch site – like viaLibri for instance – where the number of independent sellers and second-hand book offerings substantially out-number those available from the Big A, even when its new titles are added in.

But this strays, of course, from the primary focus of the story, which gaped at an incomprehensible price attached to what should have been a cheap used paperback. It is not clear how this threatened the sanity of the featured publisher, who we presume is not also a third-party seller and does not traffic in used books.

We are also warned about “the wild pricing specialists, who sell both new and secondhand copies”. I have some experience in this particular world and this is not a category of bookseller I have yet encountered – at least not one who was active as a third party bookseller who sold both new and used copies with ‘wild’ prices. This explanation comes from Guru Hariharan, a former Amazon employee who now heads a company “which develops artificial intelligence technology for retailers and brands.” Referring to these wild pricing specialists he explains that “By making these books appear scarce, they are trying to justify the exorbitant price that they have set.” If Mr. Hanrahan has indeed discovered a method for making common books appear scarce then the prospects for his company would be rosy. I wouldn’t count on it. Internet search engines now provide a definitive measure of scarcity that is visible to anyone in the market place for old books. While it might be possible to make a scarce book appear common, I have not yet learned the secret for making a common book appear scarce. When I have mastered that bit of magic I will be sure to keep it to myself.

Unless I’m too late. The Russian hackers may already have started to work.

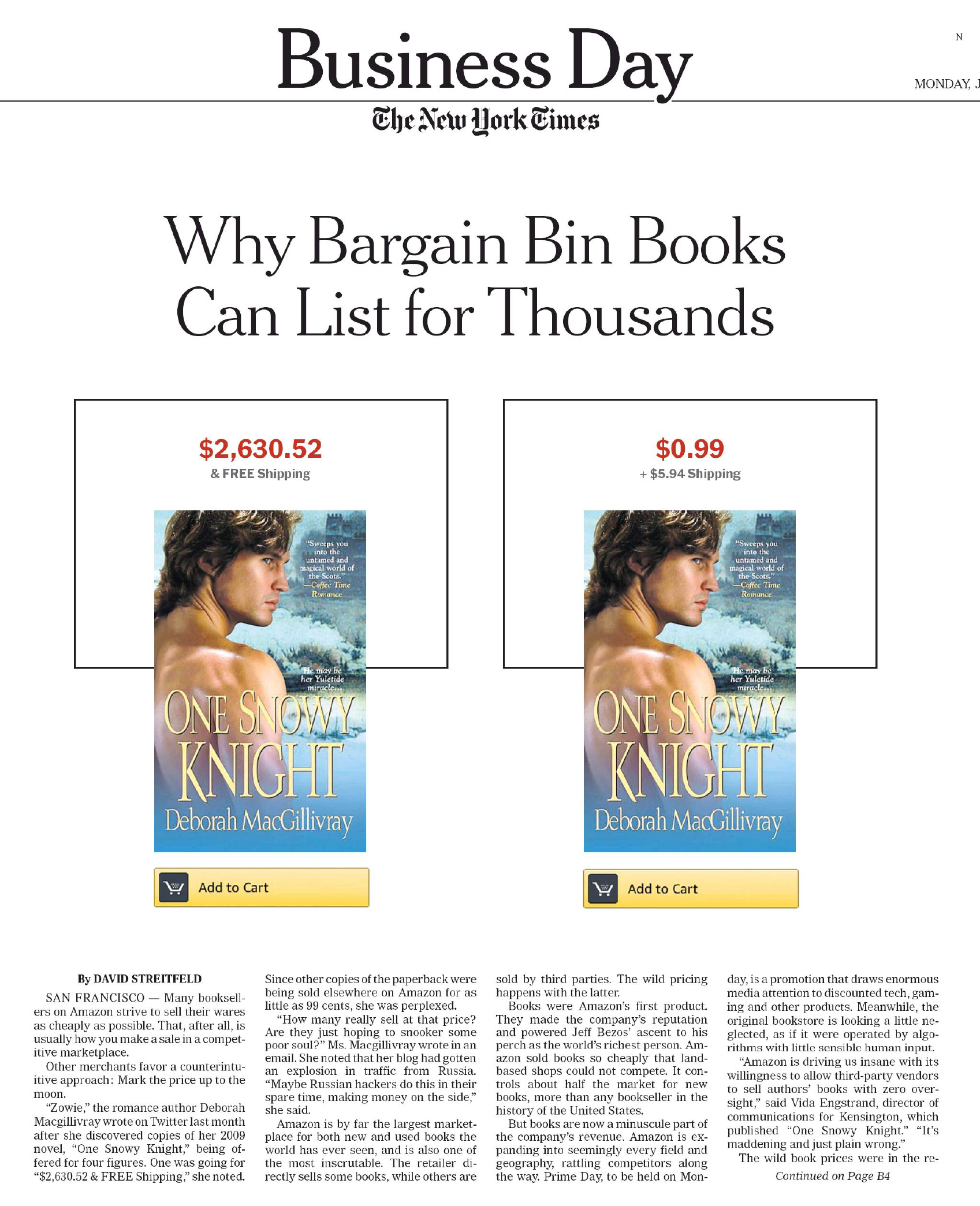

We are pleased to announce that viaLibri now includes books from eBay as part of its search results. If you look in the “Where to Search” panel in the upper right hand corner of our home page search form you will see two check boxes for eBay.com and eBay.co.uk. When these have been ticked the old, rare and out-of-print “Buy It Now” book listings from those two sites will be added to all the items from all the other sites we already search. This means that over 30 million more items have now become searchable.

We are pleased to announce that viaLibri now includes books from eBay as part of its search results. If you look in the “Where to Search” panel in the upper right hand corner of our home page search form you will see two check boxes for eBay.com and eBay.co.uk. When these have been ticked the old, rare and out-of-print “Buy It Now” book listings from those two sites will be added to all the items from all the other sites we already search. This means that over 30 million more items have now become searchable.