We are happy to report that AbeBooks and ZVAB are now available again.

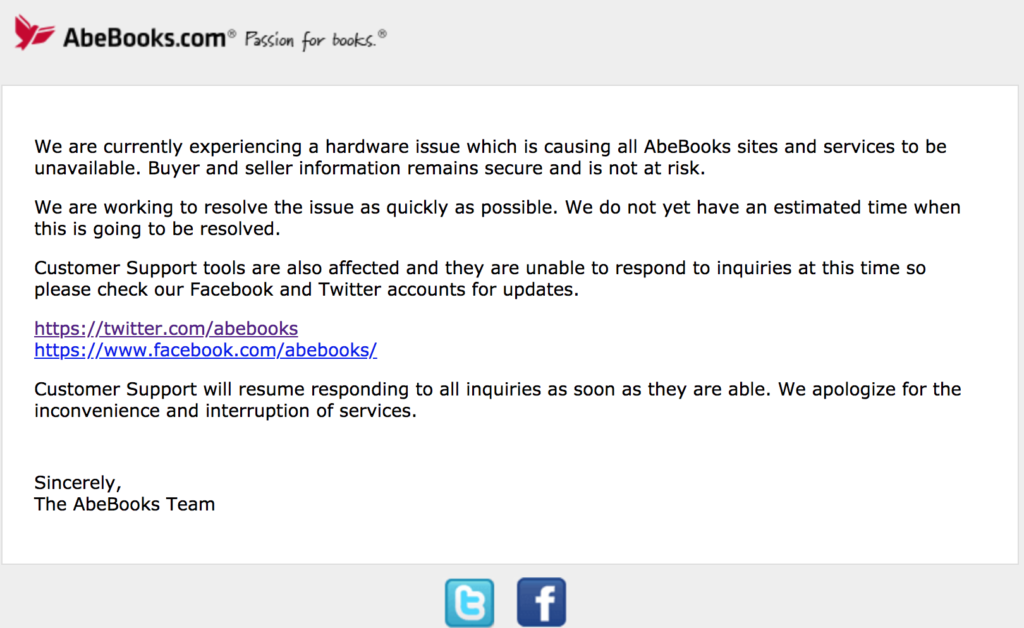

Service Interruption at AbeBooks and ZVAB

AbeBooks and ZVAB are both experiencing technical problems that have kept them offline for more than 9 hours. Unfortunately, that means that they are currently also missing from viaLibri search results and new Libribot matches will need to wait until they are back online.

Sorry for the interruption. We hope it won’t last long.

How To Find A Rare Book

I think most people now take it for granted that finding an old book isn’t very hard. Of course, this wasn’t always the case. There was a time, not too long ago, when finding even a relatively ordinary out-of-print book print involved a fair amount of effort and patience. Having already blogged about that HERE I will resist the temptation to rattle on about that subject again.

Things are very different now. If you want to find an old book today it is all very simple: just fill out a form on viaLibri, click the Search button, and then scroll through all the results. If the book you want is being offered for sale almost anywhere on the internet then our comprehensive search engine will almost surely find it for you. And you are likely to find many copies to choose from. Even on a site like viaLibri, which specifically targets the interests of collectors, the median number of results returned from each search is 14. In most cases the only challenge is deciding which copy you want to buy.

But not always. Even with the huge ocean of the internet to fish in it is also possible to search for a book and have nothing show up in the results. Although unusual, it does sometime happen that there are no copies for sale. That is when we can start talking about something being rare.

‘Rare’ is a word we have lately learned to use only with some trepidation. It was subject to much abuse in the days before online bookselling when the primary tool of measurement was nothing more certain than the experience and expertise of whoever was describing the book. Needless to say, the reliability of personal expertise can be quiet variable, and when mistaken claims of rarity have made their way into reference works and respectable bookseller catalogues it is inevitable that they will be repeated elsewhere and eventually take on the appearance of fact – all of which was possible because, for most of the books that might be encountered in the market place, there was usually no objective reference to validate or refute a claim of rarity.

Then, of course, the internet came along, and with it the perception of rarity ceased to be a matter of judgement and experience and became, instead, a simple, measurable fact. A book for which multiple copies were available online could no longer be considered rare and no bibliographic authority could make it otherwise. To much consternation and dismay, many books long regarded as “rare” were found to be otherwise. As a result, a new simpler measure established itself:

No-copies-for-sale-online = RARE

A simplistic formula for sure, but its simplicity and empirical objectivity trumped any other considerations, at least as far as the marketplace was concerned; and it was a proof available to all.

Using that criteria it turns out that a significant number of the books that people want cannot, at this moment, be found for sale online. A check in the search log for viaLibri shows that roughly 1 search in 5 returns an empty result. Moreover, while it turns out that many of the books once thought to be rare are actually not so, it has also become apparent that there are many more genuinely rare books than might previously have been imagined. When they surface they are compared with what is already for sale online. If there are no other copies found then they are far more likely to receive a careful examination than they would have in a less connected world.

At the top of this post I alluded to how easy the internet has made it to find copies of most out-of-print books. One might suppose that rare books would be different and that if the book you wanted was not currently available for sale online then there would not be much that the viaLibri could do to help you find it. But that isn’t necessarily so.

If a book is not available today that doesn’t mean that it couldn’t appear tomorrow, or next week, or six months from now. But it also doesn’t mean you have to keep coming back every day to look for it. That is what we created Libribot to do. Once your search criteria have been saved in the Wants Manager you can sit back and relax. Our persistent search bot will then start to work checking daily for new listings of the book you want. When it finds one it will send you an email with a direct link to the website where the book is being offered for sale.

You may think that you are doomed to wait a very long time if the book you are looking for is “rare” and not currently available online, but that isn’t necessarily true. It is often the case that a book cannot be found for the simple reason that the demand for it greatly exceeds the supply. In absolute terms it may not be considered rare, but in practical terms it will effectively be so. When a book of this sort appears on the market it doesn’t take long for it to be noticed, sold and to disappear. If you really want it then you will need to move fast and buy it before someone else. Libribot can help make sure you are not too late.

Even if the book is really not that rare, it may be that all the copies you find online are more expensive than what you want to pay. In that case you might resign yourself to the idea that the book is beyond your reach. You shouldn’t give up so easily. The copies you find but can’t afford may just be over-priced. They may belong to patient sellers who hope some day to get the maximum price possible. While they are waiting, however, other sellers may come along who, in return for a quick sale, will be happy to let their copy go more reasonably. All you need to do is tell Libribot and it will quickly go to work and report to you when it finds a copy with a more agreeable price. And if you tell Libribot the maximum you are prepared to pay it will continue searching for your book without bothering you about copies that don’t fit your budget.

All of which is meant to show you that if you aren’t already letting Libribot help you find books then maybe you should give it a try. Times have changed and finding rare books may now be much easier than you think.

Bibliopolis is harvest-ready (and always has been).

We recently announced some new updates to our harvesting platform that enable booksellers who have sites built with WordPress or Shopify to be included in our search results. That was news when it came out, but I didn’t want to overlook the fact that websites built by Bibliolpolis are also harvest ready. And they can be harvested with little more than a digital flick of the switch.

In fact, a few sites built by Bibliopolis were included when we first launched this feature several years ago. They participated from the start, and many more of their sites have joined us since then. They are, by far, the most numerous among the cohort of booksellers whose websites are searched directly by viaLibri.

Bibliopolis now host sites for over 300 booksellers. If you are one of them, but have not yet tried connecting your site with viaLibri, we would like to make you a special offer: a free trial period from now until the end of 2017. You can try it over the holiday period, without obligation, and if you decide to continue after that your paid subscription will not begin until January 1, 2018.

Once you have been set up the rest will happen automatically. No additional effort is required on your part. Whatever is for sale on your website will also be for sale on viaLibri with a direct link to your site. The monthly fee is only $25 ($250/year) which includes listing up to 10,000 books along with all the other standard benefits of a Premium Services subscription. There is no set-up fee and you can cancel at any point with a full refund for whatever time still remains on your subscription.

So if you have a Bibliopolis website and have wondered whether you should connect it with viaLibri (not to mention Libribot) this would be the perfect time to sign up and find out. For more information write to us here. We will be pleased to hear from you.

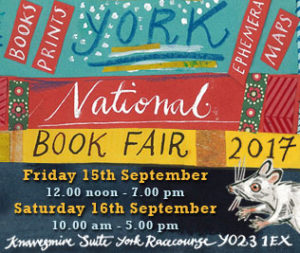

York Book Fair – See You There.

The York Book Fair is nearly upon us and eager anticipation is everywhere on the rise. With over 200 booksellers (including several from overseas) York is easily the largest antiquarian book fair in Europe. Many bibliophiles will be travelling long distances to be there when the doors open at noon on Friday the 15th. And I, as usual will, be among them.

This year, however, I will be accompanied by Alasdair North, our CTO and the digital magician behind the viaLibri curtain.

This year, however, I will be accompanied by Alasdair North, our CTO and the digital magician behind the viaLibri curtain.

Once inside, we will both be looking for books – I to resell (mostly), Al to collect. But we will both also be there with feedback about viaLibri at the top of our want lists. If anyone has questions about any of the things we do then we will be more than happy to take a break and try to answer them. That includes questions about building a new website or having links to your existing website included in our search results.

If you would like to have one of us drop by your stand during the fair just let me know. If you don’t have a stand we can meet with you in one of the cafés. If you like to plan ahead you can send a quick email to: mail@vialibri.net. If you want to get in touch just before or during the Fair then you can call me on my mobile: +44 7814 266 372. Either way we will be happy to hear from you.

viaLibri now searches Shopify and WooCommerce websites.

Over the last several years much of our energy has been focused on trying to find new and better ways to connect viaLibri directly with the websites of individual booksellers. Our ultimate goal is to provide a place where all the world’s diverse antiquarian bookselling websites can be searched as one from a single online form. Today we are happy to announce another bit of progress towards that goal: we are now able to search websites built using either Shopify or WordPress/wooCommerce.

The popularity of these two platforms with booksellers has been apparent to us for a while now. Shopify has been especially attractive to that brave cohort of sellers who are at home with digital technology and unintimidated by the idea of building a website on their own. It is easy to use and remarkably affordable. There are lots of attractive templates available and a strong support community offers advice not just on technical issues but also on useful topics like marketing and analytics.

And now, if you own a Shopify site, viaLibri is ready to search it. A few tweaks are all that it needs.

We have also been long time fans of WordPress as a platform for building attractive and flexible bookselling sites. It is now the tool of choice for many commercial website developers. We know many booksellers who have gone this route and been very pleased the results. Until recently, the one big challenge for these sites was finding a reliable ecommerce plugin with a full-featured shopping cart and the ability to handle credit card sales. The wooCommerce plugin now fills that bill and many dealers are putting it to use. Those that do now have one additional benefit: installing wooCommerce allows viaLibri to search their site.

Either option provides an excellent way to get your website connected to viaLibri and Libribot. Once you have been set up the rest will happen automatically, without any additional effort on your part. Whatever is for sale on your website will also be for sale through viaLibri with a link directly to you. The monthly fee is only $25 ($250/year) including up to 10,000 books and all the other standard benefits of a Premium Services subscription. There is no set-up fee and you can cancel at any time with a full refund for whatever period remains on your subscription.

Get in touch with us for more information

Of course, there are still other ways to have us search your website. Most custom-built sites can be easily modified to allow harvesting. For this purpose we have created a special protocol and will be happy to supply the details and answer any questions about installation. It is also possible that your existing site has already been designed to allow viaLibri harvesting, in which case all we need is your access information.

But if you do not yet have your own website perhaps now is the time to take the plunge. We will be happy to build, manage and host your new website whenever you are ready. If you would like to learn more about our LibriDirect websites you can start here:

Whatever option you might choose is fine with us. We just hope you will join us someday soon, one way or another.

Now even more books being searched by viaLibri

We have just added yet another website to our viaLibri search results. The Swedish book aggregator Bokbörsen now contributes an additional 2.4 million items to the many millions of books we already search. The great majority of these books are Swedish, so if you have any Scandinavian interests this should be welcome news.

Follow Us Now On Instagram

We are now posting regularly to Instagram. You will find us there as  @vialibri. The main focus of our postings will be photos of unusual or graphically interesting early books and related items that have been found by visitors searching on our site. We hope to do this daily, and if we fail to keep that pace it will not be due to a lack of suitable material.

@vialibri. The main focus of our postings will be photos of unusual or graphically interesting early books and related items that have been found by visitors searching on our site. We hope to do this daily, and if we fail to keep that pace it will not be due to a lack of suitable material.

If you are not yet familiar with Instagram you may want to try visiting it now. There is already a large and active group of bibliophiles from around the world sharing interesting images there. The community of rare book librarians on Instagram is particularly active and eager to pull from their vaults many treasures that would otherwise be rarely seen. @americanantiquarian is a particular favourite of ours, but they are just one of many. The number of booksellers with interesting feeds is also impressive, although we must resist having favourites there.

viaLibri now also has a new feature created specifically for the benefit of our Instagram followers. You can now go to www.vialibri.net/instagram and find a graphic grid showing all the photos we have recently posted, with the most recent ones at the top. These photos are all linked to individual pages where the complete descriptions of the pictured items are given exactly as provided by the bookseller who offered them for sale. There is even a link for purchasing the item if it has not already been sold. A link to our photo grid is also included as part of our Instagram profile, or “bio,” page so that detailed bibliographic descriptions can be found only three clicks away from your feed.

Of course, you can also check out our most recent postings just by going to the page mentioned above. That would save you from ever having to actually go to the Instagram site itself; but then you would be missing out on all the fun.

Rare Books London.

Early June has long been an important spot on the calendars of bibliophiles around the world. The original source of interest came from the fact that it always marked a unique concentration of opportunities to buy and sell books during a busy schedule of London book fairs and auctions. Those events alone were enough to lead a diverse flock of booksellers, collectors and other bibliophiles to converge annually on London, like swallows to Capistrano.

Recent years, however, have seen a greatly expanded scope and duration for what has now become known as Rare Books London. An impressive cohort of libraries and other bibliophilic groups have now joined their bookselling friends to organise an 18 day “fesitval of old and rare books” running from May 24 to June 10. In addition to the well-known book fairs and auctions, their schedule of events now includes 18 talks, 10 tours, and a special performance based on the writings of Samuel Johnson. More events will likely be added as the dates approach.

Information about everything that will be happening can be found on the RARE BOOKS LONDON website. Nearly all the events are free, but for many of them an advance ticket is required and spaces may be limited. It will be smart to reserve your places soon. Links for booking all the activities will be found on the website.

Rare Books London is a great idea and we are happy to be able to support it. If you think so too then you can also help support it and contribute to its success by posting, tweeting, pinning or just plain writing about it anywhere you can. After that I hope I will see you there.

Major Rare Book Theft Reported

A substantial theft of early and rare books has recently been reported by the Antiquarian Booksellers Association. Over 170 books from three booksellers are missing after an audacious roof-top break-in at a storage depot in suburban London. The books had been consigned for shipment to the California Book Fair scheduled for next week.

A list of missing books has been posted to the stolen books section of the ILAB website. Anyone being offered valuable early books under suspicious circumstances should check there before making any purchases. Contact details are also provided.