(I want to thank Nevine and Philippe Marchiset

for this French version of our recent blog post regarding proposed EU import regulations.)

Si une nouvelle proposition de Règlement du 13 juillet 2017 était approuvée, les collectionneurs et libraires européens pourraient avoir une fâcheuse surprise lorsqu’ils effectueront leurs premiers achats à l’importation en 2019. À partir de l’année prochaine, ils pourront être soumis à de nouvelles règles d’importation qui compliqueront considérablement le processus d’achat de livres anciens, de gravures et de manuscrits provenant de sources extérieures à l’UE. Le but de ces règles serait de lutter contre le pillage et la contrebande d’objets de fouilles et d’empêcher le financement du terrorisme par le commerce illicite de biens culturels. Bien que cette proposition soit presque entièrement présentée comme étant liée au combat contre le terrorisme, les nouvelles règles seront appliquées de manière globale et ne comprendront aucune disposition prévoyant l’exemption des biens des zones libres de conflit armé ou d’activités terroristes.

Les nouvelles règles doivent s’appliquer à un grand éventail de biens culturels, mais aucun ne sera autant impacté que les livres. Deux types de procédures existent dans la proposition :

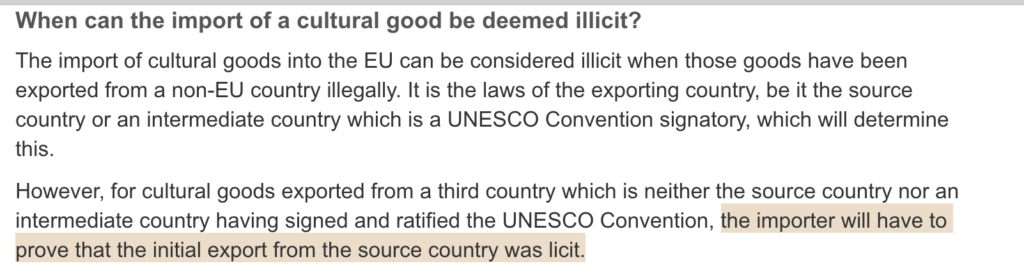

- Si un livre, une gravure ou une estampe d’un « intérêt spécial » de plus de 250 ans est présenté à l’importation dans n’importe quel État membre de l’UE, le propriétaire ou le « détenteur des biens » devra présenter une déclaration d’importation signée aux autorités douanières du pays d’entrée. La déclaration devra inclure une déclaration que les livres ont initialement été légalement exportés de leur pays source. Toutefois, dans les cas où le pays d’exportation (distinct du pays source) est une « Partie contractante de la Convention de l’UNESCO » sur les biens culturels, le détenteur devra fournir une déclaration attestant que les livres ont été exportés de ce pays, conformément à la législation et à la réglementation de ce dernier. Bien que la proposition de règlement mentionne les livres et documents d’un « intérêt spécial », elle n’en fournit aucun critère de définition, et la notion d’ « intérêt spécial » est suffisamment vague et subjective pour pouvoir inclure, en pratique, n’importe quel livre importé.

- Des exigences plus sévères s’appliquent aux incunables et aux manuscrits de plus de 250 ans. Dans ce cas, une licence d’importation doit être demandée et une documentation doit être fournie pour prouver que les biens culturels en question ont été exportés du pays source conformément à ses lois et règlements. Lorsque les marchandises en question sont exportées d’un pays autre que le pays d’origine et que le pays exportateur est signataire de la convention de l’UNESCO, alors la demande doit être accompagnée de documents et d’informations attestant que les biens culturels ont été exportés légalement conformément à la législation et à la réglementation de ce dernier. La demande doit être présentée à une «autorité compétente» (vraisemblablement un bureau de douane) qui disposera de 90 jours pour examiner la demande et l’accepter ou la rejeter. La demande pourra être rejetée si le demandeur n’est pas en mesure de démontrer que les marchandises ont été exportées du pays source « conformément à ses lois et règlements ». Dans le cas où les marchandises sont exportées d’un pays signataire de la Convention de l’UNESCO, alors la demande pourra être rejetée si les marchandises n’ont pas été exportées conformément aux lois et règlements du pays d’exportation.

Il est fastidieux de faire l’inventaire de ces règles, mais, pour nouvelles qu’elles soient, les personnes concernées (libraires, bibliophiles, voire même le grand public) devront les assimiler rapidement.

La proposition a une portée large et s’applique à de nombreuses catégories de biens culturels en plus des livres, des estampes et des manuscrits. Il existe de minces exemptions pour les biens de moins de 250 ans, de même que des dispositions spéciales pour le transit et l’exposition temporaire. Les marchandises de tous les pays source sont inclues et les importations en provenance de tous les pays non membres de l’UE devront passer par ce processus. Il n’y a pas de seuils de valeur similaires à ceux généralement appliqués à l’exportation d’objets culturels (cf. Règlement de l’UE 116/2009). Aucune distinction n’est faite entre les biens commerciaux et personnels. Rien n’indique que les citoyens de l’UE puissent importer leurs biens personnels dans l’UE sans passer par les procédures d’importation décrites. Ainsi, rien n’indique que le citoyen européen qui quittera l’Union en janvier avec des biens culturels personnels pourra revenir avec ces biens en février sans être soumis à la procédure d’importation.

Tout cela pourrait s’apparenter à un énième tracas parmi ceux qui ont vu le jour dans la foulée du 11 septembre, si seulement ce texte disposait d’une quelconque utilité dans la lutte contre le terrorisme. Il est douteux que cela se produise, du moins en ce qui concerne les livres et les manuscrits. Peut-être que les aspects réglementaires visant les objets archéologiques, les sculptures et les œuvres d’art antiques pourraient avoir un impact sur la diminution de la demande illicite et lucrative de ces objets, pour lesquels il existe un marché européen important. Toutefois, les livres, les gravures et les manuscrits sont tout à fait différents. Les livres qui ont été pillés ou saccagés par les terroristes des bibliothèques du Moyen-Orient étaient généralement de nature religieuse et écrits dans des langues sémitiques, telles que l’arabe et l’araméen. Le principal marché pour ces livres se trouve auprès d’acheteurs musulmans ou orientaux qui peuvent lire les textes et avoir un lien culturel avec eux. Si ces livres sont pillés afin de les vendre, alors c’est ce marché qui encourage leur vol. La fermeture des canaux d’exportation aux acheteurs légitimes de l’UE n’aura aucun impact sur ce marché illicite qui continuera de prospérer ailleurs. La très grande majorité des livres occidentaux soumis à ces nouvelles règles qui entreront dans l’UE n’aura pas de lien avec le marché illicite qui finance le terrorisme.

En ce qui concerne les livres, les contrôles qui ont été définis dépendent de la capacité des propriétaires/importateurs («détenteurs de biens») de prouver ou de déclarer que les marchandises importées ont été légalement exportées du pays dans lequel elles ont été créées. Cette exigence sera particulièrement problématique pour les marchands de livres et de gravures. Le libre-échange de livres existe préalablement à l’invention de l’imprimerie et l’exportation légale de livres sans documents administratifs a toujours été une pratique courante, sauf dans des cas exceptionnels. Les documents anciens d’exportation de livres n’existent pas. Ainsi, une personne qui cherche à importer un livre antérieur à 1768 dans l’UE sera soit obligée de faire une déclaration signée sur des faits qu’elle est incapable de connaître, soit, dans le cas des incunables, de fournir des documents et des informations à l’appui qu’il lui sera impossible d’obtenir. Les livres sont des objets intrinsèquement portatifs et créés dans l’espoir qu’ils seront largement distribués dans diverses parties du monde. Les circonstances selon lesquelles un livre individuel du XVIIIe siècle a pu être exporté du pays dans lequel il a été imprimé sont presque certainement inconnues. On peut supposer que la première exportation fut légale, mais la possibilité de contrebande ou de vol ne peut jamais être complètement exclue. Dans la plupart des cas, une déclaration signée affirmant qu’un tel livre a été exporté de son pays d’origine “conformément à sa législation et à sa réglementation” ne peut être que frauduleuse.

Une autre omission remarquable est l’absence d’exception lorsque le pays source et le pays d’importation est le même. Ainsi, un collectionneur allemand désireux d’acheter un incunable allemand auprès d’un libraire américain serait tenu d’obtenir une licence d’importation et de produire des « pièces justificatives et des informations attestant » que l’incunable avait été exporté conformément aux lois et règlements allemands. Même s’il ne s’agit que d’une gravure topographique de Munich d’une valeur de 50 €, l’acheteur devra soumettre une déclaration d’importateur avec une description de l’article et une déclaration signée concernant la légalité de son exportation initiale d’Allemagne.

Plus préoccupant encore est le fait que les pouvoirs dont cette nouvelle autorité d’importation sera investie ne se limitent pas au simple déni du droit d’importer. Bien que les modalités de mise en œuvre ne sont pas précisées dans le règlement tel qu’il est proposé, le communiqué de presse de la Commission européenne indique clairement que « les autorités douanières seront également habilitées à saisir et à conserver des biens (le gras est dans le texte) lorsqu’il n’aura pas pu être démontré que les biens culturels en cause ont été exportés légalement ». Ainsi, la saisie sera autorisée non seulement lorsque l’illégalité peut être prouvée, mais aussi lorsque l’absence d’illégalité ne peut pas être prouvée. Je ne pense pas avoir besoin d’énoncer les conséquences de ce nouveau pouvoir.

Le champ d’application étendu des catégories de biens visés par ces règlements est déroutant, voire dérangeant. Je ne peux que me demander si l’objectif légitime de la lutte contre le terrorisme ne s’est pas transformé en un défi général lancé à l’ensemble du marché pour les biens culturels de tous types. En dehors des livres et des manuscrits, la liste des catégories protégées comprend:

- « archives, y compris les archives phonographiques, photographiques et cinématographiques»,

- « timbres-poste, timbres fiscaux et analogues, isolés ou en collection;»

- « assemblages et montages artistiques originaux, en toutes matières »

- « Collections et spécimens rares de zoologie, de botanique, de minéralogie et d’anatomie, et objets présentant un intérêt paléontologique»

- «objets d’intérêt ethnologique »

- « objets concernant l’histoire, y compris l’histoire des sciences et des techniques, l’histoire militaire et sociale ainsi que la vie des dirigeants, penseurs, scientifiques et artistes nationaux, et les événements d’importance nationale. »

Heureusement, pour l’instant au moins, les marchandises de moins de 250 ans, quelle que soit leur catégorie, sont exemptés. Compte tenu de ce seuil, on peut se demander pourquoi les deux premières catégories ont été incluses. En effet, compte tenu des justifications antiterroristes répétées dans ces règlements, on se demande pourquoi il a été jugé nécessaire d’inclure n’importe laquelle des catégories énumérées ci-dessus. Il est difficile d’éviter de penser que la lutte contre le terrorisme, qui bénéficie d’un large soutien populaire, n’est ici qu’un prétexte pour mettre en place un système de contrôle des importations de tous les biens culturels, indépendamment de la menace, du prix ou de l’origine. Une fois ce cadre bien en place, nous ne devrions pas être surpris de voir les seuils de 250 ans périodiquement réduits, voire éliminés.

Le mémorandum explicatif de 24 pages publié par la Commission européenne exprime peu ou pas d’inquiétude quant à l’impact pesant que ces réglementations auront sur les droits de ses citoyens d’acheter et de recevoir des biens culturels, tels que des livres et des manuscrits, en provenance de l’extérieur de l’UE. La proposition ne tient quasiment pas compte de l’étendue des entraves que ces règles imposeront au commerce légitime et ignore complètement les obstacles qu’elles mettront sur le chemin de particuliers qui tentent, par exemple, de constituer des collections de livres anciens ou se livrent à des recherches historiques. Pour moi tout au moins, ce sont des activités importantes qui soutiennent les intérêts culturels de chacun et devraient être protégées plutôt que défiées. Da manière étonnante donc, le mémorandum ne révèle aucune tentative de mesure de ces activités ou d’évaluation comment elles seront affectées par les règles qui vont être imposées. Certes, le marché des livres anciens est compliqué et largement dispersé. Aucune statistique précise sur sa taille n’a été publiée. La question de savoir quelle quantité de livres et de manuscrits sur le marché libre seront assujettis au règlement proposé est ignorée. Bien que les nombres exacts ne soient pas disponibles, un examen des listes de recherches effectuées sur viaLibri indique que le nombre de livres, manuscrits et gravures antérieurs à 1768 en vente sur Internet doit dépasser les 400 000, avec une quantité sans doute plus élevée. Il est impossible de savoir combien d’entre eux sont vendus chaque année, mais sans doute s’agit-il d’un nombre à six chiffres au moins. Et la majorité d’entre eux ont une valeur inférieure à 300 $; il en existe même quelques-uns dont le prix de vente est inférieur au coût de leur expédition internationale.

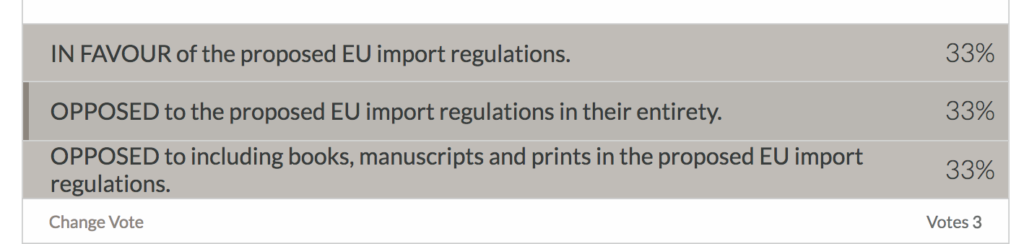

Le mémorandum prétend que, durant un processus d’évaluation de trois mois ayant commencé en octobre 2016, 305 «contributions» ont été reçues de « parties intéressées », y compris « les citoyens, les entreprises, les associations professionnelles, les représentants de groupes d’intérêts, les ONG, la société civile et les autorités publiques ». Cependant, on ignore combien de contributeurs individuels sont inclus dans ce nombre, ni quelle est leur identité. La Ligue Internationale de la Librairie Ancienne, nous le savons, n’était pas parmi eux. Ainsi, l’association professionnelle la plus importante, la plus ancienne et la plus représentative dans le domaine des livres anciens et des manuscrits n’a pas participé au processus d’évaluation. Une omission aussi grave ne peut donner confiance au résultat de ces délibérations. Heureusement, cette proposition n’a pas encore été adoptée et il est encore temps de s’en préserver. La LILA a depuis envoyé une lettre exprimant ses inquiétudes aux membres individuels du Parlement Européen qui semblent avoir une quelconque autorité sur cette proposition de loi. Il s’agit de :

Le mémorandum prétend que, durant un processus d’évaluation de trois mois ayant commencé en octobre 2016, 305 «contributions» ont été reçues de « parties intéressées », y compris « les citoyens, les entreprises, les associations professionnelles, les représentants de groupes d’intérêts, les ONG, la société civile et les autorités publiques ». Cependant, on ignore combien de contributeurs individuels sont inclus dans ce nombre, ni quelle est leur identité. La Ligue Internationale de la Librairie Ancienne, nous le savons, n’était pas parmi eux. Ainsi, l’association professionnelle la plus importante, la plus ancienne et la plus représentative dans le domaine des livres anciens et des manuscrits n’a pas participé au processus d’évaluation. Une omission aussi grave ne peut donner confiance au résultat de ces délibérations. Heureusement, cette proposition n’a pas encore été adoptée et il est encore temps de s’en préserver. La LILA a depuis envoyé une lettre exprimant ses inquiétudes aux membres individuels du Parlement Européen qui semblent avoir une quelconque autorité sur cette proposition de loi. Il s’agit de :

– Daniel DALTON (UK) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/35135.html

– Alessia Maria MOSCA (IT) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/124868.html

– Santiago FISAS AYXELÀ (ES) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/96729/SANTIAGO_FISAS+AYXELA_home.html

– Kostas CHRYSOGONOS (GR) http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/125061/KOSTAS_CHRYSOGONOS_home.html

Si ce projet vous inquiète, vous pourrez vouloir leur écrire. Je compte le faire.

________________________________________

Continuation 9/3/2018:

QUELQUES REFLÉXIONS SUPPLÉMENTAIRES sur les nouvelles règles d’importation de l’UE

Je suis encore estomaqué par l’audace dont font preuve les règles d’importation proposées par l’UE. Y a-t-il jamais eu une situation comparable où les fonctionnaires administratifs d’un pays sont autorisés à saisir des biens en raison de la compréhension qu’ils auraient des lois d’un autre pays?

Ou de plus de 100 pays?

Avec des dizaines de langues différentes?

Sur plusieurs siècles?

_______________________________________

Continuation 12/3/2018:

Des nouvelles règles pour l’importation des livres anciens et des manuscrits dans l’UE – ce ne sera pas UNE PARTIE DE PLAISIR

Dans mon précédent article sur le règlement d’importation proposés par l’UE, j’ai omis d’ajouter une description détaillée de l’épreuve que vous devrez subir lors de l’importation de biens culturels. C’est la principale préoccupation de la plupart des libraires qui m’en ont parlé. Et avec raison. D’après ce que j’ai lu jusqu’à présent, et bien que les détails ne soient pas encore complètement disponibles, il semble probable que, pour certains d’entre eux tout au moins, des tranquillisants seront nécessaires.

Après avoir à présent lu plusieurs fois la documentation disponible, voici ce que j’en comprends :

Pour les importations nécessitant une licence d’importation (incunables et “manuscrits rares” de plus de 250 ans), le “détenteur de biens” doit demander une licence d’importation auprès d’une “autorité compétente”. Le “détenteur de biens” est défini comme “la personne qui est le propriétaire des marchandises” ou qui a un “droit de disposition” similaire sur eux ou qui en a le “contrôle physique”. L’autorité compétente, bien que non définie, sera généralement un bureau de douane doté d’une compétence spécifique, avec un personnel formé à l’évaluation des biens culturels. Ni ces douanes ni ce personnel n’existent encore.

Dans des cas simples, cette demande de licence sera soumise au bureau de douane compétent accompagnée de documents prouvant que les marchandises ont été exportées légalement. L’autorité compétente disposera alors de 30 jours pour examiner la demande et requérir toute information ou documentation supplémentaire dont elle estimera avoir besoin. Une fois la demande considérée comme complète, l’autorité compétente disposera de 90 jours supplémentaires pour l’accepter ou la rejeter. Lorsque la demande sera acceptée, une licence d’importation sera émise. Les marchandises ne pourront être importées avant la présentation de la licence d’exportation. Étant donné que des dispositions sont prises pour la saisie des marchandises qui entrent dans l’UE sans licence requise, je suppose que les marchandises ne devront pas quitter le pays d’exportation avant que la licence d’exportation ne soit délivrée.

La demande devra être faite par le «détenteur de biens», ce qui signifie soit la propriété soit la possession physique. Donc, si vous êtes un résident de l’UE et que vous voulez acheter un manuscrit ancien ou un incunable auprès d’un vendeur américain, vous devrez d’abord payer votre livre, le laisser aux États-Unis, demander une licence et attendre que la licence soit émise. Alors seulement l’article vous sera expédié. Il devra être envoyé au bureau de douane compétent où il sera examiné pour s’assurer que la marchandise reçue correspond à l’article décrit dans la licence. C’est seulement à ce moment là que vous serez autorisé à recevoir votre achat.

Je devrais noter que l’article 7 fait référence à la restriction du nombre de bureaux de douane qui seront compétents pour autoriser l’entrée dans l’UE des biens culturels. Cela sous-entend que vous ferez face à des difficultés inévitables si vous vivez dans un endroit qui est loin du bureau de douane compétent. Si vous êtes comme moi, vous serez peu enclin à vouloir qu’un précieux incunable ou un manuscrit envoyé à un bureau de douane éloigné pour y être examiné vous soit renvoyé par la poste. Il n’est fait aucune mention des frais et des risques afférents à une telle expédition.

La situation est un peu plus simple pour les livres (ou imprimés) qui ne sont pas des incunables. Il s’agit d’une catégorie distincte qui nécessite une déclaration de l’importateur au lieu d’une licence d’importation. Mais les problèmes sont similaires. La déclaration devra également être présentée à un bureau de douane «compétent» qui examinera physiquement le livre pour déterminer s’il correspond à la déclaration que vous avez fournie. Il pourra également décider de conduire une «expertise», ce qui impliquera vraisemblablement un retard supplémentaire. Encore une fois, on ne sait pas très bien ce que les règlements prévoient dans le cas où vous vivez à une certaine distance du bureau de douane compétent. Est-ce que le livre sera envoyé directement aux douanes et y sera conservé jusqu’à ce que votre déclaration soit reçue et votre livre examiné ? Après cela, aurez-vous besoin de vous rendre personnellement au bureau de douane pour récupérer votre propriété, ou vous sera-t-elle envoyée par la poste ?

Aucun de ces problèmes n’est abordé de manière significative dans aucun des documents que j’ai lus, ce qui m’amène à penser que les personnes à l’origine de toute cette proposition de règlement n’ont pas encore trouvé de solution pratique. Je sais que les solutions actuellement proposées ne sont pas acceptables pour moi.

Ou est-il possible que le règlement suppose simplement que ces mesures soient toutes prises en main par des courtiers en douane, et ils auraient juste oublié de le mentionner ? Si tel est le cas, la situation est pire que nous l’imaginons.

This year, however, I will be accompanied by Alasdair North, our CTO and the digital magician behind the viaLibri curtain.

This year, however, I will be accompanied by Alasdair North, our CTO and the digital magician behind the viaLibri curtain. @vialibri

@vialibri